Hello, Jennifer Armstrong here, back with another master study. This time I am turning my attention to the great Japanese printmaker, Utagawa Hiroshige, 1797-1858. I have a framed poster of one of his prints in my dining room where I can see it every day. I love it. It's this one, called In the Kameido Tenjin Shrine, dated 1856.

There are many things I love about this image, and I will begin to break it down analytically in a moment, but first, I want to talk about this artist's influence on Western art.

Hiroshige's prints (and those of other Japanese masters) were shown in Paris beginning with the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) of 1855, after Japan reluctantly opened its doors to trade with the West. To say that the impact on European artists was electrifying is an understatement. Along with Hokusai, Hiroshige influenced every major artist of the day and the following decades - Van Gogh, Manet, Monet, Gaugin, Cassat, and so on. Copies of the prints were widely and cheaply available, and Van Gogh, for one, amassed a huge collection. These artists were already restless and dissatisfied with academic classicism, and were ready for a new way of seeing. Arguably, the Impressionist Movement would have taken a very different form without the new visual vocabulary that these woodblock prints offered. Go here for a good introduction to Japonisme and its influence on European artists - the treatment of the surface, the use of color, and so on. There haven't been many thunderbolts that had such an profound impact. Look at European paintings before 1855 and then after - it's all wildly new.

Hiroshige produced two major series of woodblock prints, one largely in landscape format, and the other in a vertical format. I want to show a few more examples of vertical Hiroshige prints and begin to highlight certain characteristics that I will then attempt to emulate. From the left: Jumantsubo Plain at Fukagawa Susaki of 1856, Suido Bridge and the Surugadai Quarter, 1857, and Kinryusan Temple at Asakusa 1856. These three, along with the one above, share some similar elements.

The first is the color. Aizuri-e literally means "blue printed picture." Hiroshige's work is very predominantly blue, and specifically, Prussian blue. These images all have extensive fields of flat blue color, which - among other things - creates a harmoniousness from one print to another through the series. There is also high chromatic contrast, especially between the blue and a dark brick red that appears in the rectangular text blocks, as well as other spots. Another characteristic of these images is the extreme contrast of scale. In each one, a relatively small object - flower, bird, kite, lantern - is shown in extreme closeup, while the remaining elements - landscape, architecture, human figures - are shown at an extreme distance. The flip-flopping of scale is fascinating. It brings the viewer into close interaction with the picture, creating the impression that the viewer is standing and taking in the view through a window or doorway. The features of each image that are ostensibly the main focus, based on title, are very far away and thus very small; the titles tell us that it is not not the large, in-your-face object dominating the composition that we are supposed to pay attention to. One of the other elements that captivated the Impressionists was the two-dimensionality of these pictures. Whereas Western artists had for generations been perfecting the illusion of three-dimensionality in painting, the Japanese prints are deliberately flat, emphasizing surface pattern and line. Objects have outlines. There is no attempt at creating a naturalistic representation of nature and objects. European art underwent a revolution after viewing these works.

My own attempt at integrating these concepts is a lot less groundbreaking (to say the least!), but it was an interesting exercise.

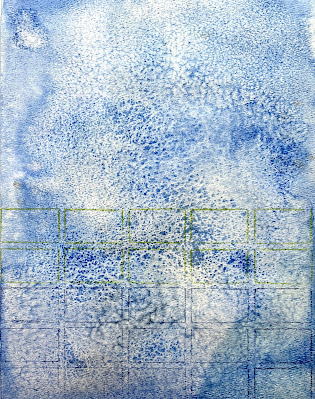

I began with a blue field. I used ultramarine and Payne's gray watercolor to approximate Prussian blue, and used salt to give the surface a grainy texture. Then, to emulate the surface pattern and two-dimensionality of the inspiration prints, I used L826 Swatch Grid Stencil by Rae Missgman and watercolor pencils to begin a grid of color blocks. This, I propose, creates an abstract landscape. Knowing I would have to have a strong red component, as well as a relatively large object to push into the distance, I stenciled the house from Club Set November 2018 by Pam Carriker onto a piece of magazine paper that had some interesting features. To get a good strong contrast I used micaceous iron oxide. I tried it a couple of ways to see which one would turn out the best.

|

| L826 Swatch Grid by Rae Missigman |

Wonderful experiment, Jennifer, and great results. Thanks for sharing this.

ReplyDeleteThis was so fascinating and fun to read!

ReplyDelete